My father reentered my life through the mail.

At the age of 14, during the summer, I returned home to find a typed letter waiting for me on my bed.

My dad had enrolled in a drug treatment program. As part of his recovery, he wrote to his family about his experiences and apologized where necessary.

Apologies were warranted.

My father had disappeared five or six years earlier, following a custody battle and then a failure to pay child support. Since then, we had moved away, and my mother had remarried and had another child. My memories of my father mostly revolved around a swimming pool that irritated my eyes, animals I adored, and an awful skin rash I contracted when he took me to Hawaii without informing my mother.

In his initial letter, he detailed his addiction and its repercussions on his life, explaining that when trouble arose, he was unable to cope, thus resorting to substances. Having completed a 28-day rehabilitation program, he intended to stay in Monterey, California — a city that historically brought him peace, reminiscent of his time at Fort Ord when he was 18.

He sealed the letter with these words: “There will be another twist to my actions, how I execute them, and the company I keep. I’m feeling more centered each day, but I didn’t fall ill in one day, and I don’t expect to fully recover in one month either. Would love to hear from you. Hope you receive this.”

I was 14. Clueless. Yet, I had a father eager to hear from me, so I replied. And then he did. And then I did. For years.

His letters wove into my life what had been missing throughout my initial 14 years. Each typewritten page, each personalized stationery with his left-handed script, patched another hollow in my heart with a semblance of love.

As I ventured into writing for my high school paper and shared my clippings with him, my father, an aspiring wordsmith craving his own printed prose, praised me with boundless enthusiasm.

At 16, he penned, “Your articles are a delight, showcasing your unwavering dedication.” At 17, a note arrived, proclaiming, “Another masterpiece! You’ve discovered your calling. I stand impressed.”

“I recognize you as a wordsmith,” his typed words on delicate vellum announced, “and any musings you wish to share on this or any other topic would be warmly welcomed.”

He acknowledged my literary flair. Above all, he cherished me.

As my high school graduation coincided with my mother’s second divorce, tuition funds were scarce. My father, now consistently supporting my mother financially, proposed sending support directly to me. This enabled my college dreams, marking me as the first in my family to earn a degree in higher education.

At 19, he bought me my most memorable vehicle, a used 1981 Honda Prelude. He outlined the terms in another letter: “If you’re going to drink, you may not drive under any circumstances. Wearing the ‘Father’ hat is still awkward, and I’m probably trying too hard, but please try to understand. I love you and respect you, all I want to know is how we can continue working on our relationship.”

Every letter ended the same: Much love, Father.

I used the car to commute to college and work and to fulfill the requirements for my major in journalism, a choice heavily influenced by my father. Once, when I mentioned switching my major to psychology, citing my love for people and desire to help them, he countered that my talent for writing was something that would help many people — and that it was a gift not everyone possessed.

Besides, he was footing the bill, so journalism it was.

When I got caught up in my social life in college, ending up with average (or subpar) grades, a letter arrived promptly, reminding me of my purpose in college.

“If being average is okay with you right now, you might as well dye your hair and move on to Burger King! Nobody ever set out on a quest to be average!” he wrote. “”The global has turn out to be a not unusual place planet and has quite tons sealed its destiny with common humans doing common work. We need excellence, and we need it from you. It will take people like you — young people with unique ideas — to take charge.”

Reader, my grades improved, if only slightly.

During college and afterward, I drove the Prelude from my apartment in Los Angeles to his home in Monterey so often, the car could almost find its way there without me. Father, his wife Karen, and I stayed up late watching movies and, after Karen went to bed, Father and I sat by the fireplace for hours and talked about the world, about writing, about life. What he didn’t share fireside showed up via mail.

It’s 2 a.m. and I have the urge to run. And I don’t mean running figuratively,” one letter read. “Sometimes, I simply want to take off suddenly. That was my pattern. It didn’t matter if things were going well or poorly, the feeling would come over me and leaving was the only thing I could think of. I’ve already run out of places to run so now I’m running in place.

In another letter, he wrote, “I’m surrounded by the summer fog. It’s damp and heavy and is keeping me indoors and away from the beach and pool. Hopefully, I’ll be able to write today. This is how it always begins.

After college, I worked as an advertising copywriter. I was 26 and making $26,000 a year writing jingles. But from my father’s letters, you’ll assume I’d received a Pulitzer.

“I assume you need to understand that I am happy with you and thrilled that you are turning into what I simplest have dreamed of turning into, a writer,” he wrote. “At least one folks will make it.

I knew writing ads for Subway sandwiches and Lee jeans didn’t make me special, but the words he sent me from his Smith-Corona did.

Like every other twenty-something, I questioned the government, policy, and the world. He had thoughts on all of it. When he rescued me from a terrible relationship in person; for nearly everything else, he guided me by snail mail and eventually, email.

“I know you are apprehensive,” he said, “which isn’t entirely a bad thing. A little reservation, concern, awareness, and passion for the details can contribute to your grace of development and critical thinking skills. Embrace your strength — writing, observing, embracing chaos, and helping others through this very ability.

He added, “As you search for something positive, thoroughly explore the corners. The true leaders are often unsung. You have inherited a mix of gifts and challenges. Choose your place, dive in, and make a meaningful impact.

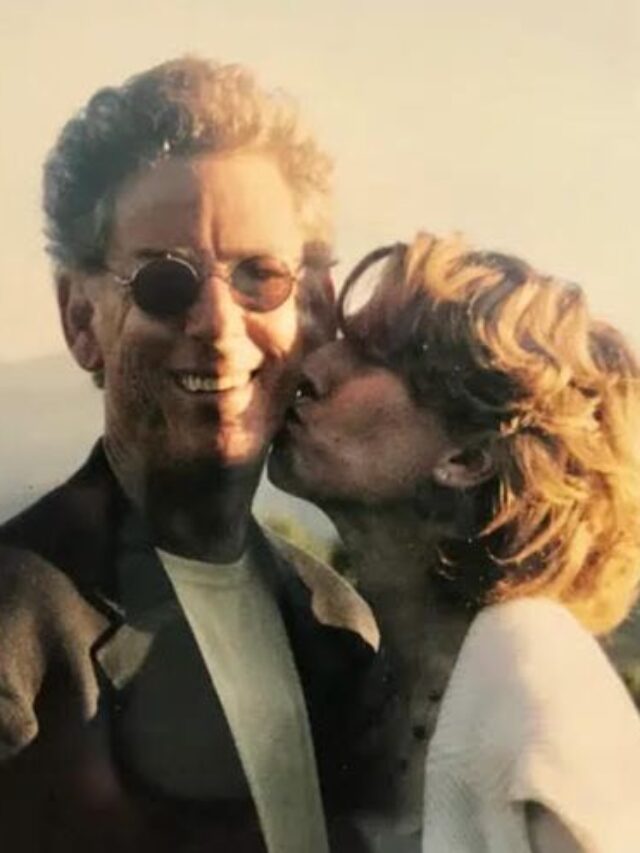

When he met my now-husband, my father was already in a dark depression, yet he emerged to the point of being joyful at my choice of partner. He became 57, suffering financially and seeking to professionally reinvent himself. The last Christmas we spent together, December 2000, he hand-delivered what I didn’t know would be his final letter.

He wrote about a new artist he had recently discovered — Eva Cassidy — and how she had told him that some moments capture our attention in a way we never forget, like when you first hear the crack of a bat or taste fresh crab or see a meteorite. He was hoping Eva could encourage me, that she could job my memory how the humanities have the electricity to try this for us.

Six months later, my dad ended his life.

After he passed away, everyone wondered if he had left a note. None had been found, but then I remembered: Indeed, he had left a note. He’d left 48 of them.

Twenty-two years later, because of those letters, my dad is still very much alive in my heart, my life, and the lives of my two children. If there comes a day I forget his love for the Dodgers, Hunter S. Thompson, or Miles Davis, if his passion for swimming in the ocean or staying curious slips my mind, all I have to do is pull out the yellow paper with the 48 precious pages on which his words remain, and I know they will bring him back to me, time and time again.